- Home

- Bridget Blankley

The Ghosts & Jamal Page 3

The Ghosts & Jamal Read online

Page 3

When Jamal left the house he looked around; he was at the edge of a village, or maybe a town, but an empty town. The houses had been built, but never lived in. This was the strangest of all the strange things that he had seen since he left home. Beyond the empty town the mountain rose up again, slowly at first then straight up like a wall. It was higher than it had seemed from the plain, and much steeper. He could see cracks and splits in the rock, but no paths. But there had to be a path – there was smoke rising from one of the cracks. Where there was smoke there were usually people. He went back to the house and collected his things. The drinks were much lighter now – there were only a few left. He was worried about carrying the cylinder up the mountain. The basket was almost worn through; if he kept dragging it there would soon be no basket at all. He decided to tie the cylinder, still wrapped in its basket, to his back. It was heavy, but he could manage, at least for a while. Jamal retied the blanket, picked up his book and headed across the deserted town, hoping to find a path when he got closer.

The path was there – not clear like the one that had led to the houses, but the ground had been walked on sometime in the past. The path rose steeply as soon as he left the last house behind and his feet slipped on the loose ground. Sometimes the path was not clear and Jamal sank to his knees in the soft soil, but when he found the path again he only sank to his ankles. It would be a hard climb. He looked at his feet, and where he was going to put his feet, but never far ahead. When he did look up, the slope seemed to go on forever, and beyond forever was the steep wall of rock that he was trying to reach. So he stopped looking up and looked down instead. If he thought about that rock he knew he’d give up, just stop walking, stay where he was and wait for the wild dogs to find him. It was just too high, too impossible. He felt as if he had been walking for days and now he knew he was about to fail. That’s why he stopped looking and stopped thinking and just walked. He let one foot sink in the hot black grit then, before the grit covered his ankles he pulled out the other foot, only for it to sink again. He would have sat in the shade to rest, but there was no shade. He would have found a better path, but this was the only one, so he just kept walking.

The path twisted back on itself, creeping up the slope like a snake hiding from an eagle. He thought of the stories his mother had told him, before she left. The one about the giant snakes that guarded the mountain, or the one about the eagle that ate fish from the River of Life and was chased away by the water spirits. They were silly stories, told to make children laugh, and Jamal had liked to hear them, because back when his mother had told them he was only a child and he still knew how to laugh. Thinking about them now made him want to cry, but at least it stopped him thinking about what he would do if his grandfather was not on this mountain.

As the climb got steeper he saw a rope, as thick as his arm and covered in the dust and grit that had blown across the path. It was lying on the path in front of him. He thought it would be useful if he needed to sleep in a tree when the wild dogs came. But there were no trees here, so he hoped the dogs would stay away, but he tried to coil the rope – just in case. He couldn’t. The rope was caught on something further up the mountain.

‘Hey!’ he shouted, the way he would have done if someone was holding the other end. He didn’t really think anyone was there. There were no footprints, but he called anyway. It was good to hear a voice, even if it was only his own. No one answered. So Jamal followed the rope, coiling it up as he climbed. Pulling on the rope made the climb easier and the knots that were tied every few steps stopped his hands from slipping. It was a useful tool to help him climb the mountain, almost as useful as the steps had been. It is a pity that I will have to take the rope with me, he thought. The next boy who climbs this mountain will not be as lucky as I am.

Then he started to laugh. He had not thought of himself as lucky before. His uncles had told him that he was unlucky. His aunties had said that when he was born all the luck had left the family and his cousins had thrown stones at him when no one was looking, saying that he was cursed and trying to make him leave the compound. He had believed them all but now he was beginning to think that he was lucky. He had not died when the ghosts came, he had not died when he fell out of the tree, he had not even died of thirst on the journey across the sand, and he had found the icebox and all the bottles of Fanta. Yes, he thought to himself, I am lucky, and I will find my grandfather and I will tell him how lucky I am.

He reached the next bend in the path and saw that the rope was tied to a metal ring that was hammered into the rock. Jamal felt guilty. He should have left the rope where it was, ready for the next traveller. He threw the loops behind him, hoping that the rope would uncoil, but it didn’t; it just tied itself in angry knots a couple of metres down the slope. Yes, he thought, I am lucky - luckier than the next person who climbs this mountain – they will have a long walk before they reach that rope.

Jamal turned back up the path and found the next rope, gave it a tug to make sure it was safe, and began climbing again. He laughed to himself, thinking how cross his uncle would have been if someone had rolled up the rope so he couldn’t use it. Then he thought how very fortunate it was that his uncle wasn’t here or he would surely have found a stick and beaten him.

It was while he was thinking about his uncle that he noticed two things. Firstly, he noticed that the air tasted different than it had done at the bottom of the mountain. It was sweeter on his tongue and lighter in his chest. It was clearer, too: he could see further, or at least he thought he could. But that couldn’t be true. Air was air, the same for the birds as the lizards and the same for Jamal. He decided that he had just opened his eyes wider because there was more to see. This was something else that he would ask Grandfather about later. Then, as if to remind himself of how things ought to be, he heard sounds. Not just the flies that had come to lay their eggs at the bottom of the mountain, but proper daytime noises – insects and birds and all the scuttling and creeping sounds that belonged to the day. There was something else, a noise that Jamal had been waiting to hear. Someone was shouting, telling him to hurry up.

‘Hey!’ he shouted. ‘Hey, where are you?’

‘You’re late. Do you think I live on air? Get a move on or you’ll regret it.’

Jamal looked around, but he couldn’t see where the voice was coming from. It was coming from the mountain, he was sure of that, but where on the mountain? The voice seemed to be everywhere, and whoever owned the voice seemed to be expecting him. They must have seen him walking up the path, maybe they had even seen him leaving the town, but Jamal couldn’t see them. Were they hiding from him, or were they so small that they were hidden, or invisible like a witch? Or had he found the ghosts? Were they waiting for him, still hungry? Jamal stopped climbing, he needed to think.

It could be a witch, but Jamal didn’t think it was. Witches were everywhere, Auntie Sheema had said so, but she had also said that they moved faster than a goat with its tail on fire. Jamal had never seen a goat with its tail on fire, but he had seen goats chased by a swarm of bees and they ran really fast, straight into the river. Jamal remembered laughing with his cousins, but that was before they said he was cursed. When he could still play with his cousins, when they would still play with him. No, the voice couldn’t belong to a witch. A witch would not have called out; a witch would have run on the wind to find him. A witch would be here by now.

It could have been something very small, an animal spirit or the sort of devil that could hide in an eggshell, but Jamal didn’t think it was. Such a small spirit would have a small voice and the voice he had heard was strong. Far away, but loud.

Jamal had heard that some mountains were alive – they were great spirits that protected the people who lived near them – but the voice wasn’t deep enough to be a mountain. And, Jamal thought, this mountain could not have a spirit living in it because it had not protected the people who had waited at the bottom.

He was left with two choices: he had found whe

re the ghosts lived, or there was a man hiding in the mountain, a man who had found the way to make his voice echo where there were no walls. If he had found the ghosts, then what did they want with him? He had no soul, they could not eat him. That meant that when he reached them they would still be hungry. Did he want to meet angry ghosts? Would they let him escape? Would they tell him what they wanted? He wasn’t sure. It could also be a man, a man who had lit a fire and who had found a way to make his voice loud, like the voices on the radio. Jamal needed to know; he needed to be prepared before he followed the voice.

‘Smoke,’ he said. ‘I need to see the smoke.’ He got up and looked up at the mountain again.

‘Why did you stop, stupid boy?’ shouted the voice. ‘Get up here now. I told you I was hungry.’

Jamal stared up at the cracks in the mountain, trying to remember where the smoke had been. He found it, almost straight ahead but not quite. It was grey, definitely grey, not yellow like the ghost smoke. There was a man hiding in the mountain. A man who was alive, like Jamal. He grabbed the rope and started climbing – almost running, if you counted pulling yourself up a steep slope covered with slippery gravel and loose stones as running. He reached the end of the rope and the end of the slope. There was a narrow strip of flat ground before the vertical rock rose in front of him.

He could see that people had been there before, lots of people. They had brought things and left things. Warnings and offerings and rubbish, so much rubbish. If this was where his grandfather lived then his grandfather was not a tidy person. Jamal was a tidy person. He swept his hut every day – he swept outside as well – and he washed his clothes and his blankets. He was not clean now – he had walked too much and had too little water – but usually he was clean. He didn’t like being dirty; his skin itched and his eyes were sore. He hoped that he would get a chance to wash himself soon. He looked at the rubbish and the flags and the offerings, trying to work out where the man was hiding.

The Old Man in the Cave

He smelt the fire and walked towards the smell till he could see the flames. Soon he could see an old man sitting, almost naked, next to the fire. As he got closer there was another smell. It was disgusting – it made his stomach turn. He hoped the smell didn’t come from the old man, but it did. He wanted to find his grandfather but he wasn’t sure if he wanted to be related to this strange, smelly old man. He wondered what to say. He hadn’t seen his grandfather since his mother had died, and that was a long time ago. How could he be sure that this was his grandfather and how should he ask without sounding disrespectful? He was still thinking what to say when the old man spoke.

‘Where have you been?’ His voice was deep, almost deep enough to make the rocks shake. ‘You took your time. I watched, you kept stopping. Didn’t you hear me call?’

‘I’m sorry.’ Jamal could hear that his voice sounded like a mouse squeaking in a thunderstorm. ‘I tried to come quickly. I think you are my grandfather.’

‘Do you now? And why is that? Do you know how many wives I’ve had, how many children? I don’t even know how many grandchildren there might be. How should I know if you are one of them? I don’t think you are, you’re not strong like me. What have you brought?’

Jamal had no gift. He had not thought to bring anything from home, he’d only thought about getting away, and about the ghosts. He couldn’t stop thinking about the ghosts; he was still thinking about them.

‘I’m sorry, Grandfather, my gift is very small, only these drinks.’

The old man, who might have been Jamal’s grandfather, snatched the bottles. He drank one straight away, then threw the empty bottle so that it joined the piles of rubbish that Jamal had seen earlier. Then the old man opened the second bottle, drinking that the same way. He held up the last bottle.

‘Are you thirsty?’ the old man asked.

Jamal thought he was offering to share the last drink, but he was not that sort of grandfather.

‘If you are, you can get yourself a drink of water – there is half a bottle in the cave. Put this next to the water. I’ll drink it later.’

Jamal took the bottle – it was Sprite. He had only taken two bottles of Sprite from the ice box and he had been saving this one. Reluctantly he headed for the cave. It was cooler there, but too dark, after the daylight outside. He paused by the entrance, letting his eyes get used to the blackness. It was good that he did: there were three – no, four – uneven steps that led to the main part of the cave. Jamal saw where the old man slept and where he kept his clothes. He saw rows of pots and boxes and bottles that smelt even worse than the old man did. Jamal didn’t go too close; he imagined what they might contain – dead snakes and monkey bones and … no, he didn’t want to think what else might be there. He saw the water bottle, next to a bowl of dried-up stew that had been kept for too long. Jamal put the Sprite next to the bowl and picked up the water. It did not look fresh either, but Jamal was from the country and he knew water was not always fresh, so he tipped the bottle up.

‘Ugh!’ He spat it out. Jamal wasn’t even sure it was water; it burnt his mouth and made his eyes run.

‘Good, eh?’ The old man slapped him on the back. ‘Now don’t waste it, boy, you won’t get water like that at home.’ The old man laughed. ‘Now bring the bowl. Let’s eat.’

Jamal put the bottle down and picked up the bowl of what he thought was last week’s lunch then followed the old man back out to the fire.

‘So now we fill our bellies. What else have you got in there? Tinned meat; fresh? Or this year’s yams ready to roast?’

There were flies buzzing around the stew and Jamal shooed them away.

‘They’re back then. I wished them away and they went. Now you’ve brought them back. Not very clever, are you, boy? Bringing the flies back to the mountain.’

Jamal said nothing; he wasn’t ready to ask about the ghosts yet. Ask why they had come and why they went away and what that had to do with the flies. So he just nodded.

‘Now, boy, why do you think I’m your grandfather?’ The old man poked at the fire, adding logs ready for the yams that he thought were in Jamal’s bag. ‘Who was your father? Your mother? Where are you from?’

Jamal tried to answer his questions, but he didn’t know his father and he wasn’t sure of the name of the town that was near the compound. But he told the old man what he could and he described his journey – not the people, just the places. He didn’t feel like talking about the people.

‘Could be,’ the old man said, chewing some betel. ‘There was a girl called Asha, I think. It’s hard to remember the girls, you know. Too many of them.’ He spat out the remains of the nut. The red spittle hit the bowl then hissed in the fire as it fell in a sticky blob into the flames. ‘My third wife, Nnedi, she had a girl. I think she was called Asha. You said I went to the funeral - when was that?’

‘About three years ago, maybe four. I was only small,’ Jamal said.

‘You’re still small, boy, still small, but you’re right, you could be my grandson.’ The old man slapped Jamal on the back again. ‘What did you say your name was? Jamal? Strange name, not one I recognise. Why did your mother give you that name? What does it mean? Runt of the litter, I think.’

The old man started to cough.

‘Something to do with the flies,’ his grandfather said. ‘The cough came when the flies left. It’ll go soon, now the flies are back.’

Jamal couldn’t understand why his grandfather said that. It was a bad cough, the sort of cough that comes before dying, not the sort of cough that was caused by flies.

Jamal did not want to see any more dying, so he turned away and walked back to the cave.

When he returned his grandfather had stopped coughing. He was looking in Jamal’s basket, the one that was tied inside the cloth. He did not look happy.

‘What’s this?’ He was pointing at the cylinder, then he looked at Jamal and kicked the cylinder away.

‘What good is that to an old man with a

n empty belly?’

Jamal started to explain, but his grandfather wasn’t listening.

‘What’s wrong with you? Do you think we can eat this, this poison? You come up here, talking of children and grandchildren, bringing no gifts, no food, only poison. Are you trying to kill me?’

Jamal was confused; he hadn’t expected his grandfather to be like this. He thought his grandfather would give him breakfast and warm tea and tell him why the ghosts had come.

‘I did not come to kill you. You are my grandfather. I am your daughter’s son, you said so. I came for your help. Why would I come all this way to poison you?’

‘How can I help you when my belly’s empty? If there is no food for me, there is none for you either, boy. Don’t think I will give you any of this. That is not hospitality. Sharing food, that is hospitality. But you, you come here expecting food when you bring nothing. Tell me, boy, what else have you got hidden there? There is something else, I can see it.’

Jamal shook his head, afraid he might say the wrong thing and make his grandfather shout again. This was not the sort of grandfather he was hoping to find.

His grandfather stirred the pot of stew on the fire. Jamal was hungry, but the stew smelt bad, and he was sure that some of the old man’s spit had landed in it earlier.

‘There’s none for you, so don’t look hungry.’ His grandfather added half of the bottle of water to the bowl. ‘Yes, you could be Asha’s boy – you are ugly like her, and ungrateful. Well, I was pleased when she left and I’ll be pleased when you leave. So just show me what else you’ve got there and get on your way.’

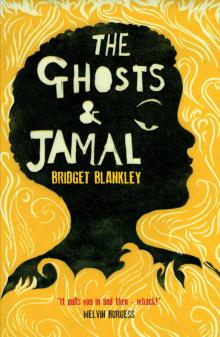

The Ghosts & Jamal

The Ghosts & Jamal