- Home

- Bridget Blankley

The Ghosts & Jamal Page 2

The Ghosts & Jamal Read online

Page 2

I have to get to the mountain, Jamal thought, or I’ll die, and there was no point in leaving home just to die somewhere else.

Jamal started to walk, thinking, I need to get to Grandfather. And that was all he thought about as he walked. He stopped thinking about the scratches on his legs or his sore wrist or how hungry he felt. Every step was a step closer to his grandfather and that was the only thing he had to remember. When his grandfather had come to the compound he had told Jamal that he lived two days’ walk away, on the Mountain Without God. Was this the right mountain? Jamal knew that he should go to the mountain; he knew he had to find somewhere to live. He just hoped that he’d found the right mountain.

Jamal couldn’t actually remember much about his grandfather, or why he had left Jamal with his aunties instead of taking him back to the mountain, but that didn’t matter. Jamal had somewhere to go. And there was someone who would look after him and help him to find where the ghosts lived.

Although he had to stop three times to sit down because he was feeling dizzy, he reached the rocks before the sun was overhead. He might have stayed where he was and forgotten about the mountain if it hadn’t been for his grandfather. Jamal just knew that his grandfather would be waiting for him somewhere on the mountain.

The rocks were flat and smooth. Jamal hadn’t realised this when he saw them from the tree. Also, there were paths between them. Paths worn by hundreds of feet crossing them over hundreds of years. It was cooler here too. There were more trees and more shade, and Jamal could even hear a river, although he couldn’t see it. The path twisted and snaked like a liana stretching between the trees. Jamal was in a hurry, but he was too weak to clamber over the rocks. He followed the path. It was the slowest way to climb, only rising one step for every five or six, but it was easy. Old people, sick people, fat mammies and small babies, they all used the steps while the young and the strong clambered over the rocks. He wanted to stay on the path.

The steps seemed welcoming, but they weren’t; the ghosts had been here too. They were gone now, those soul-seekers. Right in front of Jamal, before the steps really started, they had left one of their red canisters. But the ghosts had gone – none of the yellow trails or choking odours remained. But they had definitely been here.

Jamal hesitated. He wanted to examine the red canister – to know more about the ghosts and what they were looking for. He also wanted to stay alive. Was there a ghost still in the canister, waiting for the others to return? Maybe waiting for another soul. After all, everyone else who had been here was dead, their souls had already gone. But Jamal didn’t have a soul, so he would be safe. He needed to know, but he was afraid to know. He stood rocking backwards and forwards, not sure what to do next.

He sat down, feeling alone, wanting to cry. It was unfair; he wanted to cry but he was too thirsty, his body wouldn’t waste water on tears. He decided that he would cry later, and maybe scream and shout and throw rocks at trees. Just so everyone, the old Gods and the spirits and the ghosts and the God in his book would all know that he was being treated unfairly. But before he could do any of these things he would have to find something to drink. And before that, he would look at the red canister. This was where the ghosts lived. If Jamal wanted to stop the ghosts, he would have to find out why they had come. He knew that any ghost left in the canister would kill him, but it was time to be brave, to be a man. If Allah willed it, Jamal would die. If he did not, Jamal would live and maybe stop the ghosts from killing anyone else.

Jamal edged forward, tapping the canister with a stick. It rolled away, reached the edge of the first step then stopped, as if the ghost inside was deciding what to do next. Jamal held his breath and waited. It toppled onto the soil. The sound, bell-like and innocent, echoed across the mountains. The ring reminded Jamal of a single, lonely cicada. One sound when there should have been hundreds.

Secrets and Stories

Jamal took a step towards the canister – not too close, but close enough to see inside. As it rolled, smoke slid lazily onto the soil like a small blind snake slipping under a stone. It wasn’t ordinary smoke – the colour was wrong. Jamal knew how to change smoke – burning goat skins made it dark and burnt button weeds made it go yellow and smell of ants – but he didn’t know how you’d make smoke this colour. It was the colour of an old man’s pee. He wondered if this was the colour of dying. The ghosts killed people, and the old men he’d met had all died. Even his mum’s eyes, when she died, had been yellow like the smoke. He’d looked at her eyes and he’d wanted to close them, but his uncles wouldn’t let him. They had shooed him away, whispering to each other when they thought he wasn’t listening.

It was after his mum died and his grandfather left, taking all the palm wine from his uncle’s store, that everyone told Jamal that he was unlucky. That was when they built his hut right away from the compound.

His eyes began to prickle, not from the smoke that was sneaking down the hill, slipping through the cracks and into the ground. No, this time his eyes were stinging with tears. He sat on the step, digging little holes in the soil with his stick.

‘Stupid ghosts.’ His voice sounded like a radio turned up too loud, distorted and crackly. He couldn’t even shout. How would anyone know he was here if he could only whisper? Jamal looked around. It didn’t matter – there was no one here. Even the ghosts had better places to be.

‘No time to feel sorry for yourself, Jamal,’ he said. ‘That was then, this is now. You are not a boy, crying like a baby.’ It worked, he knew what he had to do. He wiped his nose on his arm and went back to where the cylinder had landed.

He bent down, looking at it closely. The first thing he noticed was that it wasn’t completely red. It had signs and marks all over it, writing too. But the writing wasn’t clear and anyway, Jamal couldn’t read. He understood the pictures though. Pictures were there to tell stories, like the pictures on the shops in town – the man having his hair cut at the barber’s shop and the steaming cup painted on the wall of the teashop. You didn’t need words when there were pictures. There was a fish on the cylinder. A fish with a line through it. Not a very good fish, more like the carvings that children make, or the beads that you sometimes found hidden in the soil. It was definitely meant to be a fish but Jamal was not sure why it was crossed out. Was it bad for fish, or made from fish? Perhaps the cross was meant to be a fishing net.

There were other pictures too: a tree, some bones and another cross. It was an odd mix of images. What was the story? Maybe if you caught fish in a net, then the ancestors who lived in the trees would be angry. Maybe if you didn’t catch fish then the ghosts would come and haunt the trees. Or were the ghosts looking for fish, or trees or bones? What good were pictures if they didn’t make sense?

Jamal decided that these pictures were meant to confuse. The ghosts had secrets and they wanted only the right people to understand them. Jamal knew that he wasn’t one of the right people. He was too unimportant to be the sort of person ghosts would want to share their stories with. Then he remembered his grandfather. It was time to find him.

His aunties had said that Jamal’s grandfather was a powerful man. They were all afraid of him. If he was very powerful and if Jamal could find him, maybe he would understand the story on the canister. If he knew what story was being told, maybe he could give the ghosts what they were looking for. Then they might go away.

So, Jamal had two – no, three – problems that he needed to solve before he could even think about finding the ghosts.

First, he needed to find water. He needed to do that before he did anything else. After that, he needed to find something that would hold the red canister. It was too heavy to carry up the mountain in his arms, and he was not as good at balancing things on his head as his aunties were.

Then he had to find Grandfather and that was the hardest thing that he had to do. Because this might not be the right mountain, and even if it were, it looked as though it was covered in caves. And Grandfather could be livin

g in any one of them.

Between Jamal and the top of the mountain were all the people whom the ghosts had killed. He would have to find a way to get around them, or over them. Jamal was pleased that he didn’t have to solve that problem quite yet. He would leave the red canister where it was and go hunting for water. There was a stream near the steps that led down to the river, but the fish and the frogs that should have been swimming in it had all died. The birds that had been feeding on the frogs had all died and had fallen into the stream. Jamal wondered if the ghosts were swimming in the river, among the dead things. Even the wriggling mosquito larvae were dead. If the ghosts were so hungry that they had taken the life from mosquitos then they would surely take Jamal’s life if he drank from the river. Jamal looked around. There had to be something to drink; there were so many people here, they wouldn’t all have been thirsty. There was no market, so the people hadn’t come to shop; they’d come to walk up the mountain.

Jamal saw that some people had been selling drinks – Sprite and Fanta in small bottles and juices in packets. He liked Fanta. The Imam would bring bottles of Fanta when he visited, leaving a crate in the compound for his cousins. A whole crate, less one bottle. That bottle he would share with Jamal while Auntie cooked dinner. He licked his lips; they were cracked and sore. The ice had melted but the icebox was full. But Jamal wasn’t quite sure what he should do. He needed a drink. He’d finished the water he had brought with him a long time ago, before he had left the spirit tracks. He could fill his bottle from the melted ice, but what if the ghosts had been in the ice? Would the water still be safe to drink?

Jamal wasn’t used to being thirsty; there was always water at home – water and fufu and stew. He didn’t have any money. His uncle had kept everyone’s money. He kept it in a tin that he hid under the thorn bushes. Jamal knew where it was, but he hadn’t thought to take it, even though Uncle was dead. So Jamal had no money and nothing to sell. He didn’t want to take a drink – that would be stealing and he knew that was wrong. But he needed a drink; he needed it very much. He looked at the icebox and the drinks and he looked at the auntie, half fallen from her stool. Now he was worried again. He started rocking, like he did when he needed to think. It was as if he was trying to pull the answers from somewhere deep inside him. But the answers stayed hidden. Jamal wanted someone to tell him what to do. He was unlucky, a spirit boy, not someone who was used to making decisions.

Jamal looked around – the spirits were returning, he was sure of it. He could smell the sweet nutmeg on their breath and hear their voices buzzing in his ears. He leant against a tree trunk, keeping himself hidden, even though he knew the spirits would still find him. He was thinking about the bottles in the icebox when the spirits wound their smoky selves around his eyes and he sank into an uneasy blackness.

The spirits tortured Jamal for most of the day. He woke when the sun had burnt itself out. He woke to something else as well. Flies. There were flies everywhere, filling the air and settling on the bodies. The ghosts must have been satisfied at last. That’s good, Jamal thought. I couldn’t stop the ghosts from coming but at least I’ve chased them away. The mountain might come back to life, even if all the people don’t.

Just then Jamal heard swifts chattering at the sudden feast of flies. Other birds would be here soon, and animals too, if they had escaped the ghosts. Jamal had seen the wild dogs fighting over goats and he wanted to be away before they came. He had no time to think, he had to start walking again. He went over to the drink seller. He looked at her. She was covered in flies and their black-tipped eggs. Obviously, she didn’t need his money. Even if he caught the ghosts she wouldn’t want to be chased back into this body.

He pushed as many drinks as he could into a cloth and tied it, like a lumpy baby, to his back. Then he took one more bottle; it was warm, but he didn’t care. He opened the bottle, smiling as the gas escaped, hissing like an angry beetle. Jamal drank the sticky liquid then dropped the bottle and took an extra one to drink on the way. Maybe if another boy came along, he would be able to pick up the bottle and sell it. Maybe that was a way to pay for the drink, leaving the bottle for someone else.

He needed to be able to carry the cylinder so he took a basket from one of the dead aunties, though he had to push her arms to free the bag. He was sure he shouldn’t have – he’d been told not to touch other people – but he needed the basket and this auntie wouldn’t know that he had pulled at her hands. This was the second time in his life that he had stolen something and it was much easier than the first. When he stole the Fanta he had worried so much that the spirits had heard him and returned. But this time it was easy. He saw the basket in the fat auntie’s hand and reasoned that she must have been very wealthy to have grown so fat. Maybe she had several baskets at home and would think it good to give a basket to a poor boy like him.

There were bananas in the basket, so he emptied them on the floor before he took it. He thought about eating some of the bananas, but there were no ants on them and ants ate everything. Jamal was sure that his grandfather would share his food, and he would know what food was safe. He must know almost everything if all these people had been going to climb the mountain to see him. Jamal was pleased to have such a wise relation. He pushed the canister, with the ghost riddles painted on the side, into his basket and pulled the basket behind him. It was much heavier than he expected. He tried to balance it on his head like his cousins did, but the basket wobbled and he was afraid that the canister would fall out and roll back down the hill. He gave up and pulled the basket once more, bumping it over the stones and the people on the path. He took care not to actually tread on anyone, but it was hard to control the bag. When he started walking up the path he apologised to the aunties and uncles lying on the ground, but soon he had apologised so much to no one in particular, that he just pulled his basket over the people and walked as quickly as he could. He wanted to be away from this place.

He wanted to reach somewhere safe where he didn’t have to keep deciding what to do. And he wanted someone else to do some thinking. He was sure that if only he could find his grandfather, he wouldn’t have to keep on racking his brains. Grandfather would know how to stop the ghosts and how to make things normal again. He couldn’t quite remember what his grandfather looked like – after all, he’d only seen him once before – but he remembered Grandfather’s voice. It was loud and deep and chased away the witches that walked across the roofs at night. He was definitely the sort of man who would know what to do next.

How High is a Mountain?

The further Jamal walked, the fewer bodies he saw. That’s good, he thought; the ghosts don’t like to climb. This was the first thing he’d learnt about the ghosts. He decided to tell Grandfather, when he found him. In the meantime, he kept walking, dragging his basket up the steps.

The steps stopped suddenly, just as the path turned back on itself. Jamal stopped too. It was dark and he could hear the wild dogs at the bottom of the path, but everything was quiet around him. The ground was flat and rough – not solid rock like the steps, but gritty, like the roads near the market at home. There were buildings all around. Houses – white concrete houses with no doors or windows and vines growing through the walls. Jamal couldn’t understand why these houses were empty. There were no bodies, no signs of ghosts, but no signs of people either. Strangely, Jamal felt more afraid here than he had at the bottom of the mountain, but it was dark and he was tired so he crept towards the closest house. He listened. There was no noise inside.

‘Hello?’

He waited.

‘Hello?’

Silence.

‘Hello Auntie, Uncle, may I enter?’

He stepped inside. Snap! Jamal dropped his bag and jumped backwards, tripping as a black … what? Something, he couldn’t tell what! Then silence again. A moment later something flew past him. It brushed against his face and he screamed. Then again and again. Jamal was embarrassed – he had screamed like a parrot in a trap. They were bat

s, only bats that had been hiding inside the house.

Jamal wrinkled his nose - the smell was awful. The bats had lived here for a long time and the floor was covered in their droppings. But only three had left; where were the rest? Jamal had walked by the hollow trees where they roosted and he knew that this much poo meant a lot of bats. He moved to the next house. It was quieter, less smelly. He went inside, but not too far. Who knew what was hiding in this house.

Jamal stayed near the door. He untied the drinks from his back and leant against the wall. He would wait until it was light before he looked for his grandfather. The mountain was too big and too dangerous to climb in the dark. He drank one of the bottles of Fanta, then another, and another, until he felt sick. He threw an empty bottle outside. It smashed. Somehow the noise made Jamal feel less alone. A human noise in the silence. He burped, loudly, as loudly as he could. The noise echoed in the concrete room. If I lived here, Jamal thought, I would drink Fanta and burp all the time. Next minute he fell asleep, sliding down the wall and curling into a ball. He was still asleep when the bats returned to their roosts.

When he woke up he was hungry. But he had no food. If only he had known this would happen when he was at the bottom of the mountain, but he hadn’t. He had another drink instead, though he was getting fed up with Fanta – he wanted a cool drink of water straight from a stream. The drinks he had were too sweet; they seemed to make him even thirstier. That was another thing to ask his grandfather. How can you feel even thirstier after you have had a drink? There were so many things that he’d never thought of before. He wondered if he would have known these things if he had been to school. His uncles had said that there was no point in sending him to school. That he was too stupid and too strange. He wondered if that was true. It probably was – after all, his uncles wouldn’t have lied. Perhaps if he could find the ghosts and get them to leave him alone then he would be able to go to school. He decided not to tell anyone about wanting to go to school; he knew that even Grandfather would laugh if he shared this secret.

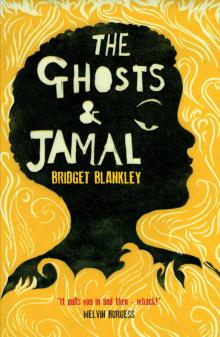

The Ghosts & Jamal

The Ghosts & Jamal