- Home

- Bridget Blankley

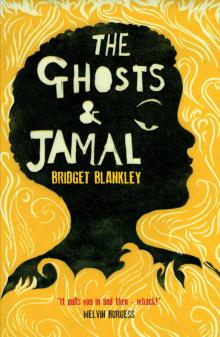

The Ghosts & Jamal

The Ghosts & Jamal Read online

Bridget Blankley spent most of her early life in Nigeria. She worked as an engineer, educator, and full-time carer before coming late to writing; her first piece of fiction was published in her early 50s. Her fiction, however, has since gone on to win several prizes including 2013 Winchester Writing Can be Murder and Commonword Children’s Writing Competition 2016. In the same year, she was runner up for the Thomas Gray Anniversary Poetry Competition as well as runner up for the 2017 Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize.

Bridget has an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is delighted to support the work of The National Autistic Society with the publication of The Ghosts & Jamal. Bridget lives in Southampton. @BridgetBlankley bridgetblankley.com

The Ghosts & Jamal

Bridget Blankley

Dedicated to the memory of Gertrude Soemers, a devoted nurse and wonderful person who helped me with many of the details connected with Jamal’s illness, and who was always there for me.

Ghosts

It was light when Jamal woke, but no one was up and about. Morning should have been the noisiest, the busiest time of day, but nothing was moving. He sat trying to decide if he was really awake, looking at the walls of the hut, checking that everything was where it ought to be, straining to hear the sounds of the camp. Straining to hear, what? There was nothing to hear. Last night’s attack was definitely over and the hut seemed OK, and – even better – Jamal was still alive, so that was all good, but the silence was definitely not good.

If it was light he should hear children squabbling, uncles finishing their prayers and aunties starting breakfast and hushing their babies, but there was nothing. He couldn’t even hear the ear-buzzing hum that usually followed the bombs. Everywhere was totally, utterly silent.

Jamal realised just how frightened he was; frightened, but not stupid, so he didn’t call out. Instead he sat perfectly still, holding his breath. He didn’t know who was outside and he didn’t know the reason for the silence, but Jamal was pretty sure that someone out there had caused it. He also knew that he didn’t want to meet them. He had no idea what to do next. But he did know that being alone was a bad idea, that calling out was a worse idea and that waiting to be found was the worst idea yet. So he sat very still, trying not to make a noise, trying to disappear into the shadows and trying to be certain of the right direction to take. He was thirteen, almost a man – not that anyone thought so, he was still treated like a baby – but he knew he was a man. A man who could work out what to do.

As he sat there, hardly breathing, the early morning smoke made him sneeze. Jamal froze; had he given himself away? Slowly, he uncrossed his legs, easing the pins-and-needles from his ankles. If anyone was watching they’d know where he was now. He waited, expecting them to come into his hut.

Nothing happened.

He decided to go outside. His hut had been built on an outcrop of rock where the soil was too thin to grow crops. If he went outside he would be able to look down into the family compound and see what was wrong. Jamal pulled a blanket round him – right over his head so his face was hidden. It was an unimportant act – a habit – but that day it would save his life …

There was too much smoke. It didn’t tickle his nose any more, it was grabbing at his throat, squeezing the air into his stomach in wrenching coughs. He was choking, gasping acid breaths till suddenly his ears were bursting with noise. He fell to the ground, his blanket slipping across his twitching body, hiding his face under the heavy cloth. That was when the pick-up drove past.

‘This one’s gone, boys, or nearly gone. Don’t waste the grenades, we’re not finished yet.’

The truck accelerated up the hill taking its masked passengers away from Jamal and on to another target.

Jamal’s hut was outside the compound. Not far outside – he could still hear the talking, see the children playing and even smell the bread baking on the stones – but it was not part of the village. He was close, but not too close. Jamal was unlucky, marked by spirits, so he wasn’t allowed to enter the compound.

He hadn’t been abandoned and chased away from the village like his mother. The Imam had seen to that. He told Jamal’s family that Jamal was ill and they had a duty to care for him. But his family didn’t want Jamal close and as soon as the Imam left they built a hut as far away as they dared and Jamal had lived there ever since. Food was sent out with small children who scampered up the slope to Jamal’s hut, skirting in circles to make sure that no shadow from Jamal, or his hut, fell on them. Water was fetched from the well and delivered in much the same way. Overall, although he was excluded from their society, Jamal’s family had ensured that he would at least survive.

Now, as Jamal struggled to stand, he looked towards the compound and realised that his family would no longer be able to help him. The thorn hedge that surrounded the compound was intact. The animals were in the corral and his family were scattered about the compound, just where they ought to be. His aunties near the fires, their children clustered by the huts and his uncles in the centre of the compound, gathered around a bright red canister. As far as Jamal could tell, only two things were wrong: a dirty yellow vapour was streaming from the canister and everyone in the compound was dead.

The smoke that made Jamal cough and choke in his hut was partly from the contents of the canister and partly from Auntie Sheema, who had fallen onto the cooking fire. Jamal hesitated; leaving Auntie to burn seemed wrong, but she would not want Jamal to touch her, even to save her from the fire. He wasn’t sure what to do. Jamal’s life had been simple: to eat what he was given, keep himself clean, sweep his hut and bury his waste. He had a role in the family: he had to draw bad spirits away from the compound and let them feed on him. Thus he would twitch and shake when the spirits came, rolling in dirt or knocking into the walls, while his aunties and uncles and cousins stayed safe. Jamal hated being visited by spirits, but he accepted his lot. The spirits came to him, punished him and made him ill, but they left his family alone.

Today that hadn’t happened. Jamal had slept soundly when the spirits came. Ghosts were escaping from the canister and they had killed his family. He stumbled, his eyes burning, smoke and tears stealing his sight. He called out to the ghosts, begging them to leave the compound and to come to him; but the ghosts didn’t listen, they just hovered in the hollows, snaking through the huts, hungrily searching for souls. Jamal knew he couldn’t help. Soul-seekers had no use for Jamal, he had no soul. His grandfather had told him that, on the day they buried his mother.

He turned away, picked up the can that held his water and shuffled east following the churned tracks that the spirits had left. The yellow smoke from the canister was drifting in that direction. The ghosts must have had their fill. There was no need for them to stay in the compound. Jamal decided to follow them, find out where they were going, or maybe where they lived. That sounded like a good scheme. There was nothing he could do here; maybe he could find the home of the ghosts. But what then? Would they listen to him? And if they did, could he save his family, or had the ghosts already taken their souls?

He had no plan. For as long as he could remember he hadn’t needed to plan. His family had cared for him and he had protected his family. Now he had nothing, so he walked. His red blanket and a copy of the Qur’an, which he couldn’t read, were the only familiar things in this unfamiliar world. He needed the blanket to hide from the ghosts. He wasn’t quite sure why he needed the Qur’an, but the Imam had told him to keep it by his side, and the Imam was a nice man. He would come to the hut and talk to Jamal, and sometimes he would shave the hair from his head so it didn’t itch. Yes, Jamal thought, the Imam is a good man, so I shall take the book with me, to please him.

A Walk Across the Sand

Jama

l was hungry. His family had died before breakfast so nothing had been brought up to his hut. He knew that the aunties picked plants to put in the stews, but they had never taken Jamal with them. He didn’t know which plants he should eat so he didn’t eat any, just in case they made him sick. But he was so hungry that when he passed a bush covered in red berries he thought that being sick might be better than being hungry. He was about to pick the fruit when he saw that there were dead birds in the bush, six of them. It was strange because there were no flies round the birds and no ants on their bodies. But Jamal didn’t think about the flies, not till much later. He just decided to leave the berries, even though they looked sweet. The birds might have been attacked by the ghosts or the berries might have been poisonous – Jamal didn’t know. But he didn’t want to risk the fruit killing him as well. He kept walking.

Maybe he could find another family. A family who were plagued by spirits and who would look after him if he kept the ghosts away. Jamal thought that would be his best plan. He would have to go a long way from home though, because if they heard that his family had died they wouldn’t allow him to stay. That was too much bad luck for a boy to bring with him. He kept walking, following the tracks in the dust until the sun was high. He had never been this way before, not on his own. He wondered if he should have stayed at home and forgotten about finding the ghosts’ home.

He could see a compound about an hour’s walk away. There were no signs of people – no smoke, no goats, nothing. It looked abandoned, or worse, but Jamal needed help, so he pushed through the scrub towards the huts. The spirit tracks were less clear, but they were still there. Wherever the red dust broke through the rocks Jamal could see the tracks. He shivered a little and the air seemed to stick in his chest, whistling and wheezing to escape as he forced each breath. He felt as if one of the spirits had its hand on his shoulder, pushing him to the ground. So he pulled his blanket across his face, breathing the familiar smells of wool and smoke, keeping the ghosts away from his mouth. He wanted to reach the compound – there would be water there – but between him and the compound were more ghosts. They were snaking up the hill towards him and Jamal knew he needed to leave before the ghosts smothered him like they’d smothered everyone else. He struggled, trying to stand, taking one step then another, trying to escape into the fresh air while all the time the ghosts were grabbing at him, pulling him back to where everything had died. The comforting taste of his mother’s blanket between his teeth seemed to protect him as he forced his legs forward. Step, stagger, stumble, step, fall, stand – slowly escaping back up the hill where the ghosts couldn’t reach him. When he couldn’t walk any more, he sat, leaning his back against a tree.

What was it doing there, standing on its own with nothing growing around it? Jamal might have spent time trying to work out why the tree hadn’t been cut down, but he didn’t; he was too tired and too thirsty. He drank the last of his water and closed his eyes. He knew he shouldn’t sleep – he was out in the open, away from the fires and the thorn fences that keep the animals away – but he’d been walking for so long and it was so quiet that he just wanted to sleep. He felt warm and comfortable and he wrapped his mother’s blanket around him to keep the flies from his face. But there were no flies. Jamal stopped feeling tired. There were always flies: even at night when the brown flies slept, the mosquitos came. Suddenly the tree didn’t feel safe any more. He wasn’t sure why – it was something to do with the flies, but he couldn’t quite work out what. But he knew he had to go and find somewhere safer.

The tree was tall – taller than the trees near home – but it had thick branches, even low down. Jamal thought that he’d be able to see a long way from the top of this tree. He tried to climb, but he needed both hands. He was forced to leave his Qur’an behind. He wondered what the Imam would say; he had told Jamal to keep it with him, to look after it like a new-laid egg, and now he was planning to go without it. Jamal said to himself that it would be OK to leave the book on the ground, as long as he could see where it was. He put the book a little way from the tree and started to climb. It was no use: he still couldn’t get further than the first branch. He couldn’t climb and keep his blanket wrapped around him. It slipped from his shoulders and twisted itself round his ankles. He nearly fell. So he dropped the blanket. Jamal was wearing blue shorts, the ones his cousin had outgrown. He had never climbed trees, but he knew his cousin could climb – Jamal had watched him from the corner of his hut. If Ham can climb then I can climb, thought Jamal. After all, I must be as big as he was, if I am wearing his shorts.

Jamal decided that he would climb every tree he passed from then on – there weren’t many on the plain – and stopping at each tree would make the journey seem shorter. He pulled himself through the branches, clinging tightly as his feet slipped, even when the thorns ripped the skin on his hands. It was strange, the higher he climbed the fewer thorns there were. It was like a stockade to keep people away from the sky he thought, as he reached a strong forked branch near the top of the tree. Sitting there he could see everything, the whole world – or at least he imagined it must be the whole world. He could see the plain that he had walked across and he could see that the land began to rise ahead of him. It kept rising to where there were more trees. Beyond the trees there were rocks and beyond the rocks was a mountain. Jamal had never seen mountains before, not close up, only their blue-grey line on the horizon. This mountain was a bit different; it wasn’t part of a line of mountains. It stood on its own. It was as if a giant had thrown a calabash when he’d finished drinking and it had stuck, neck down in the green land. Of course, he didn’t believe in giants. They were not like witches or the bog trolls that lived by the river and pulled careless children under the water. Giants were just made-up things to make little children behave, but still, this mountain looked odd, a great grey boulder rising out of the plain. Jamal was sure that there was something special about it. There had to be. So special that an important man like his grandfather would choose to live there.

He had heard his uncles talking about a mountain without God. He was not sure what that meant – how could God be kept from a mountain, or anywhere else? The Imam had told him that God was everywhere and knew everything. His Qur’an would have the answers, he was sure of that. The Imam had said that all the answers to the questions of man were there. ‘But what is the good of answers that are hidden?’ he would ask his grandfather. Surely a man like his grandfather would have learnt to read.

There was something else about the mountain, he was sure there was. Something that he was meant to remember. He would think about that when he was walking to the mountain. Thinking about the mountain would stop him remembering his aunties and their fish soups and groundnut stews – red with chillies and tomatoes. His mouth watered when he thought of fatty palm weevils, crisply fried crickets and – when the rains came – nutty termites with maize pudding. He shook his head, trying to drive thoughts of food away. But he imagined he could smell smoky roast goat. He couldn’t, of course. There were no goats – and no one to cook them. But when you’re hungry and alone it’s easier to imagine your favourite food than to remember that your favourite things have all gone.

‘Think about the mountain,’ he said aloud. ‘Think about climbing that enormous mountain.’ His voice sounded too quiet in the empty air and he slid down the tree, grabbing at branches. It was much harder to climb down than it had been to climb up. He was nearly at the bottom. There was one more branch to go when he heard the ghosts hissing in his ears. They must have seen him sitting in the tree and been waiting till he climbed down. He should have kept his blanket so he could have hidden. And he should have kept quiet instead of shouting out loud. Jamal smelt their breath and felt them push his chest and pinch his nose. Then he fell from the tree.

The ghosts must have just wanted to tease him by reminding him that they were there. Because they left him quickly. When he sat up it was still light and still quiet. He felt sick, like he always did, and very

thirsty and his belly grumbled with hunger. But there was no water left to drink and no food in his pockets. He would just have to stay thirsty till he reached the mountain and he could find his grandfather. He was very sore. His back ached and he could feel the blood where the branches had scratched at his skin. His wrist was sore too. Very sore. He could hardly move it. He would have to tie his blanket round his neck, and use his good hand to carry the Qur’an. There was even blood on his blue shorts. When he found some water he would wash them, or flies would smell the blood and land on his legs.

He looked up at the tree. It had been good to climb, as good as anything he had ever done. It had not been so good to fall, but he would recover. All in all, he thought, it was worth the fall, just to have climbed the tree.

He turned towards the mountain, away from where he had come, away from home. He had thought about walking to the mountain and now he would do it, although it looked a long way away and the sun would set soon. So he would have to start walking tomorrow. He wished that he had a fire and a bowl of Auntie’s stew, and enough thorns to make a fence, but he had nothing. Being next to a tree was better than being alone on the plain so he wrapped himself in his blanket and slept, his head on his book so that he was as close to it as he could be.

In the morning, he was cold and stiff. He could hardly move his left wrist, and soil and twigs had stuck to the cuts on his back. He tried to pick at the scabs to clean them, but he couldn’t reach. I must get to a river and wash, he thought. But he didn’t want to think about the river, because when he did, he remembered that he wanted a drink. He knew he had to get to the mountain. There would be water there. Jamal wasn’t certain how he knew but he was quite sure.

As he eased himself up he saw that the leaves were damp. Jamal thought about eating the leaves – there were no dead birds on this tree – but he was scared they might be poisonous. He knew many trees made poison to keep the grubs from eating them. He decided to get as much water as he could from the leaves and drink that. The water won’t be poisoned, he thought. It wasn’t, but there was only half a mouthful, hardly enough to wet his tongue. He felt even more thirsty than he did before.

The Ghosts & Jamal

The Ghosts & Jamal